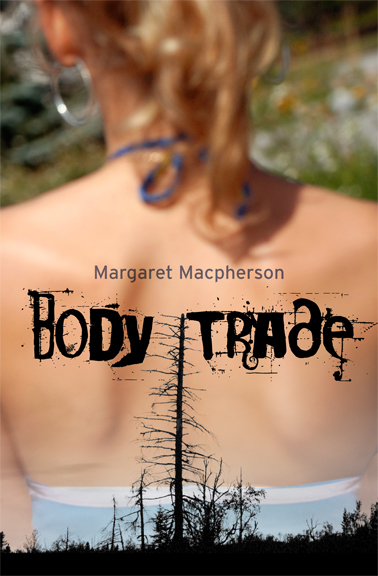

“Here’s the opening paragraph of Margaret Macpherson’s new novel, Body Trade:

“The body is gone. People are milling around the church basement, visiting, relieved and happy that Lloyd can go directly into the ground. No hanging with the other stiffs in the ice house, waiting for the permafrost thaw. Nope, none of that for Lloyd. He’s somehow managed a summer accident. Cleaner. Faster. Probably the only clean thing Lloyd ever did.”

Now that is a great opening for a novel. It’s swift, it’s clean and it establishes a strong narrative voice, that being Tanya, the 20-something tough girl who many at the funeral suspect had something to do with Lloyd’s death. Yes, she was having a fairly clumsy affair with Lloyd and, yes, she was working the bar the night he headed off drunk in his truck, but, no, she didn’t kill him.

That doesn’t stop Tanya from deciding that maybe a little time away from Yellowknife and the Northwest Territories might just do her and Lloyd’s grieving widow a world of good.

Meanwhile, we meet Rosie, an Inuit girl, barely more than a teenager, living unhappily in residential school. Her parents are dead, her brother’s in jail and she’s been apprehended by social services.

Rosie and Tanya meet with the usual young person awkwardness and discover a common discomfort with their surroundings and a desire to get out.

That’s all it takes, and the two gather up their work money, roll out Tanya’s Rambler and head south, destination Mexico just because they’ve heard of it and it’s warm.”

“Two women in Yellowknife decide, on the spur of the moment, to drop everything, leave their jobs and head to Mexico. Tanya, the one with the Rambler, is a world-weary white woman working in the residential school; her travelling companion is Rosie, a 17-year-old native girl. Both carry the burden of a painful past. Off they go.

It is 1973, the year after the northern crash of a mercy flight, with bush pilot Marten Hartwell having emerged as the sole survivor. This novel by Edmonton author Margaret Macpherson focuses on the journey of the two women, with the crash as a parallel story. By weaving together the two narratives, one factual, the other fictional, Macpherson delivers an intriguing tale with contemporary themes that ring true more than 40 years later.

Hartwell was taking a nurse, a pregnant Inuk woman and a 14-yearold Inuk boy from Cambridge Bay to Yellowknife for medical help. When the plane crashed, the nurse and woman died on impact, and the boy lived for nearly three weeks by eating lichen. Hartwell was eventually rescued. The subsequent inquiry, loaded with controversy and followed by the international press, is “blowing through Yellowknife like a bad spring snowstorm.” The extraordinary lengths people go to for survival is a central theme of Body Trade.

On the long road trip with many detours, Tanya and Rosie form a bond, which strengthens as they drive south and get into all sorts of predicaments. When their car breaks down, they hitchhike and sleep in all-night laundromats and make a happy detour to Disneyland. But dangers lurk ahead. As two women adrift, with only vague plans, they are open to both adventure and misadventure, mostly in the form of ne’er-do-well men they hook up with along the way. Eventually they make it to Mazatlan.

Macpherson’s story is ambitious, and tackles many issues: racism, class struggles, female friendship and white-aboriginal realities. Some of these efforts work, others don’t. The clash of the white and aboriginal points of view is sharply defined, and Macpherson effectively uses the metaphor of the landscape to describe these differences. For the whites, “the school year in Yellowknife is like the Mackenzie, one huge muddy brown river of kids that flows fast and furious in and out to school, needing to be fed morning, noon and night.” As the women drive south, Rosie marks down in her notebook the names of all the rivers they cross. The rivers came first, then the towns, she explains to Tanya.

Rosie’s trusting, sweet nature and her total lack of cynicism are no defence against the threats of the world. But through her, the reader learns a lot of the Indian way of life. Tanya, though more experienced, makes serious errors in judgment. The combination does not add up to a happy ending.

A hellhole in the jungles of Belize is the ultimate destination for these two women, and like the pilot Hartwell, they have to find a way to stay alive.

Body Trade is an unusual story that offers a unique look at the Canadian North and the people who live in it, escape from it or survive its harsh realities.”

“Two young women decide to blow their small, northern Canadian town and head south: the United States, Mexico and finally, Belize. The year is 1972.

A carefree adventure becomes deadly serious for Tanya (experienced, pragmatic, overly confident) and Rosie (younger, naive, overly sensitive) in Margaret Macpherson’s new novel, Body Trade (Signature Editions). Impossible decisions must be made.

“I’ve always had the title in my head,” Macpherson says. “I wanted to talk about the flesh trade. The idea of physical, human flesh.

“Tanya’s a body girl,” she adds. “Tanya needs to be in charge, in control. She was a fun character to write. I loved her energy, her fuck-you attitude.

“But I like Rosie, too. She’s so pure. Sex is a very tender thing to her.”

As the two head further south, the novel becomes increasingly dark.

“I like to call it Thelma and Louise meets Apocalypse Now,” Macpherson says. “They are in the Heart of Darkness.

“It was a tough book to write, but I had to write it.””

“Body Trade begins with two exquisitely drawn characters. Tanya Price is the quintessential bad girl who runs away, on many levels, from Hope (BC). At 22 years old, her outlook is informed by “temporary relationships” as daughter, girlfriend and friend—she understands completely how the female body is commodified. Rosie Gladue is her opposite, a naive 17-year-old virgin grounded spiritually by the teachings of northern Canada’s Dogrib people.

Tanya and Rosie meet in 1972 at a Yellowknife residential school, where Tanya is the daytime secretary and Rosie is a cleaner. Rosie’s grandmother and mother are now dead and her brother is in jail. The young women are drawn together by their desire to escape Yellowknife. For Rosie, their connection is also spiritual, something she accepts without question. Tanya, however, never fully honours or understands that bond. The opening chapters set up an angel/whore dichotomy, and despite Macpherson’s beautifully poetic prose, some readers may find this approach blatant, especially later in the novel where the narrative offers repeated examples of virgin sacrifice. But one of Body Trade’s triumphs is its collage of contradictions.

Tanya and Rosie leave Yellowknife driven by the promise of a warm winter on the beaches of Mexico. They journey south in a 1960 Rambler until it breaks down in San Francisco. They bus around Mexico, staying in the cheapest—not the safest—places they can find. When they run out of money, they travel in the back of a truck to the newly independent Belize, lured by the promise of jobs at a plush resort. Instead, they become captives.

Macpherson uses a life-threatening situation to build to the novel’s climax. The scenario will no doubt provoke readers to think of other, much-publicized examples of violence against women. As it concludes, the novel takes some unexpected turns and culminates in an astonishing denouement. Readers will have to decide for themselves whether the ending is believable.

Throughout the narrative, this skilled author builds strong and at times gut-wrenching tension, using the threat of sexual exploitation in the sinister corners of San Francisco, East LA, Mexico City, Guadalajara and, finally, Placencia (Belize). That Macpherson manages to weave in larger subjects such as betrayal, cultural erasure, disappeared women and the effects of imperialism only highlights her abilities.

Body Trade is Macpherson’s seventh book; she has also published four works of non-fiction, a collection of short stories and a novel. Macpherson shares with Robert Kroetsch, Rudy Wiebe and Aritha van Herk an intimate love of landscape, but Body Trade reaches beyond our borders to tell a universal tale.”

“If contemporary fiction is fighting for its life, its followers ought to be on the lookout for writers who are brave enough to swim against the current tide.

And if a writer has genuine star quality, a sharper, deeper radiance than most, then he or she ought to be identified and celebrated without delay.

Time may be of the essence. Margaret Macpherson, a relatively unknown Maritime-born Albertan, is such a writer, and Body Trade, her seventh book and second novel, is the proof. She writes with the psychological insight of Carol Shields, the gravitas of Margaret Atwood, the poetic reflexes of Earl Birney and the earthy eroticism of Leonard Cohen, but her voice remains uniquely her own.

Body Trade, released by the Winnipeg literary house Signature Editions, is a haunting road novel best described as a poetic thriller grounded in the real world.

Macpherson also has one distinct advantage: her natural territory is comparatively untouched as literary landscape. She is a non-aboriginal native of the Northwest Territories, known vaguely to Canadians as “the North” and to readers around the world, if at all, as a new planet of undefined stretches of white space — snow, ice, fog, the cold. There is powerful mystery here, and Macpherson knows it.

That is where her story begins, when two young women come together in their desperation to escape what could only be their bleak northern futures.

Tanya is white, mid-20s, a hard case who has earned enough money as a bar maid to point her aging Rambler to the sun and beaches of Mexico; Rosie is Dogrib, still in her teens, a product of residential schools, and orphaned except for a brother in jail.

For her, a companion and a car are the equivalent of a magic carpet.

It’s 1972 and feminist energy is new, full of confidence and promise. The two girls, an unpredictable, mixed-race Canadian variation of Thelma and Louise, set off on a journey that will descend into a hell on earth beyond their combined ability to imagine.

The hostility of extreme cold slowly gives way to the suffocation of extreme heat, and the cultural exploitation of the northern forces to those of the South. There is little to smile at in Body Trade.

Macpherson goes back and forth between this fictional journey and another borrowed from actual history. In November 1972, a Beechcraft carrying native medical patients and piloted by bush pilot Martin Hartwell crash landed.

The only survivors, two men, one white and one native, were also forced to make choices that dictated whether they would live or die. In both the fictional and historical narratives, there will be only one survivor who will pay an unspeakable price for a second chance at life.

Body Trade keeps a tightening grip on its readers, racing to a final few chapters in which the heart pounds inevitably faster. The ending is an unexpected shock to the spirit.

The recent book marketing campaign that claimed that the world needs more Canada still lingers. To that should be added that Canada needs more Margaret Macpherson and writers like her, who offer sophisticated, substantive and poetic novels sure to keep an appetite for fiction alive and very well indeed.”

“Good versus evil, coming of age, first love—all articulately presented in a gripping narrative–what more could you want in a novel? Edmonton’s Margaret Macpherson has published non-fiction (Nellie McClung: Voice for the Voiceless) and short stories (Perilous Departures), and her story-telling skills are now impressively showcased in Released, her first novel published by Winnipeg’s own Signature Editions.

It’s the story of Ruth Callis, the youngest of five children who, remarkably enough, grow up in a happy home. Macpherson splits her narrative into two alternating accounts, one giving the trials and tribulations of Ruth’s growing-up years, and the other dealing with her love affair, at age 20, with Ian Bowen, a somewhat mysterious fellow 16 years her senior.

At the most critical point of the novel, the two accounts converge.

The Callis family lives in a Northwest Territories town, where the father works for a gold-mining company. Though the mother doesn’t exactly like it up North, she hasn’t let it embitter her, and the kids seem to get along well with both parents.

Much is made of Ruthie’s childhood dental problems and the family affectionately calls her Toothie. She seems well adjusted, and she has at least two good friends, one of whom is an aboriginal girl called Jax.

Ruthie’s innocence and gullibility become clear in this latter relationship, but Jax doesn’t take advantage of her. Later, though, when Jax is no longer around, Ruthie—at age 14—falls under the influence of the local evangelical church, and the young men who call themselves Elders.

“If I ever wanted to be like them,” she muses, “I was going to have to start getting serious about the stuff around me.” Meaning she should divest herself of her possessions.

And so she puts together a bagful of her clothes and gives it to the thrift store in town. She also starts to fast, believing she’ll only be acceptable to God when she loses weight. Brainwashed as she is, Ruthie is unruffled by her schoolmates who call her “Jesus freak,” and she fails to see the harm the Elders may do to her—but, eventually, she does.

Meanwhile, in the parallel narrative, the older Ruth, now at university in the Maritimes, goes to a bar one night and meets Ian.

“I’m not the type to fantasize about kissing a stranger but it happens like a brief shock, a pop-up cartoon picture of us kissing, my tongue touching that plump lower lip.”

Ian has a past he doesn’t speak about but, impressionable as she is, she feels as wholeheartedly attracted to him as she once was to God. It’s only a matter of time until Ian will disappoint her, but Ruthie seems unable or unwilling to read the warning signs—she has to experience whatever Ian has in store for her.

One of the best sequences tells of their hitchhiking trip to Sudbury, where her parents are now living—and to Toronto.

Macpherson packs a wallop with her scenes of violence, but even after those, poor Ruthie seems to want to see some good in the person if not the deed.

The author opens and closes the novel with Ruthie’s situation some years after the events of the story, a frame that seems rather unnecessary to the book’s effectiveness, just as Ruthie’s sojourn to Australia seems tacked on.

But, as a whole, Released is absorbing—you’re pulling for Ruthie no matter what she does. This is an accomplished and ultimately satisfying first novel. ”

“…In Released, Margaret Macpherson creates no less than an epic story about Ruth, this made especially remarkable by the fact that Ruth only comes into her twenties within the time span of the novel. While Carroll’s novel [Body Contact] is more entertaining, Macpherson’s is sobering, as Ruth continually teeters between creative and destructive forces in her life. Hearkening back to the biblical namesake, Ruth is loyal, kind, and compassionate, and this may very well prove to be her undoing. A source of guilt for “Ruth the Tooth” is how she enters the world, born with teeth and causing pain to her mother during breast feeding. Her girlhood is marked by two significant factors; numerous painful dental procedures are mitigated by her saving grace, a strong connection and friendship with Jax. when the “summer of Jax” is complete, the reader wants her to reappear perhaps as inexplicably as she disappears, and Ruth will unconsciously search for her in future years. Naivete, guilt, and an ascetic bent draw Ruth to religious fanaticism in her adolescence, and to the centrepiece relationship of the novel, with her boyfriend Ian. He introduces Ruth to romance, poetry, alcohol, and eventually violence and a cycle of abuse: “I don’t know real pain. Ian does, of course. That’s what defines him. That’s what draws me in.”

Macpherson portrays a believably regression of Ruth and Ian’s relationship, a downward spiral from carefree adventures to Ruth enduring torturous acts. Especially wrenching is that through all of Ian’s abuse, she is absolutely unguided, unprotected, and unadvised. She receives no protection from ehr parents, friends, roommates, professors, or church. What makes this particular narrative different from other tales of young girls falling for the wrong boy, only to come to misery, atonement, and healing? In a speech to Ian, Ruth’s resilience stems from her ability to forgive. She is real, honest, wrong, innocent, closed, trusting, blind, courageous, ignorant, open, young, and caring.

In all, Released is about searching for the sacred, whether through God, a romantic relationship, or a friendship. ”

“Making Peace

Author says book is about forgiveness

When talking about her first novel, Released, and its protagonist, Ruth Callis, author Margaret Macpherson makes one thing clear: when she creates fiction; the characters come from her imagination.

“The joy of fiction is using the writer’s imagination. This is my character’s life. Not my life. I created Ruth, and she tells her story,” she says. “I never felt like I was carrying around the weight of the world, telling Ruth’s story.”

“I get up ad make sandwiches for lunch; then I enter her world. I engage and disengage. I have to.”

Even though Macpherson goes beyond writing what she knows, she enjoys writing what she knows, she enjoys writing about where she’s been. Treks through Bermuda, Central America, Mexico, Europe, and Australia all left a mark on Released.

“The book is all over the map: the East Coast, the Noth, Sudbury, Australia. And I really enjoyed writing about Yellowknife. Finding settings was the easy part.”

The award-winning author says that love, betrayal, and redemption are fundamental to all human characters. But Released emphasizes the element of forgiveness.

“To come to full humanity is to forgive. Anger doesn’t get you anywhere. My book is more a lesson than a warning. It’s about the notion that one must forgive in order to find freedom,” explains Macpherson.

Provocatively original, Released offers a series of life lessons, learned the hard way by the narrator, Ruth, who revisits her past after reading a newspaper clipping about a man who saved a drowning boy. Is this Ian, her abusive ex-boyfriend? Reflections, questions, and memories are triggered, pressuring Ruth to make peace with her past.

Macpherson says Released questions the moral impact of religion and personal domination. “Why do people get themselves into situations of violence? I found that the answer, at least for this character, lay in the indoctrination of selflessness. She is set up by the church. She sheds her sense of self. In the pretense of being selfless, she tries to take the place of God and become Ian’s savior.”

Macpherson wants people to believe in Ruth’s struggle. “I want them to see themselves. And if I can make them think–what more could I ask?”

Chronicling the human condition is not entirely new for this Edmonton author who has previously published one book of short fiction as well as several books of non-fiction. With a degree in creative writing from the University of British Columbia, Macpherson says her fundamental goal of writing a novel never wavered, although it took over a decade.

“I spent 11 years working on and off, writing this book. In the interim, I wrote five other books, so I wasn’t working on it exclusively. But I had to find a way to tell the story of violence against women. I kept going back to the story,” she says.

“It wouldn’t leave me alone.”

“Feeling just a little down? Feeling just a little blue?

Try lunch with Edmonton writer Margaret Macpherson, the deliriously happy author of Perilous Departures, a collection of short stories that marks her debut as a writer of fiction. She’s so happy her book is out, she’s a tonic for whatever ails you.

“But please don’t call the stories ‘sunny’,” the decidedly sunny Macpherson says over a lunch interview. “They’re not sunny.”

She prefers to call them quietly optimistic, most of them anyway, and she’s right. They tell stories of survival, understanding and compassion. They’re accessible but multi-layered, sometimes subtly funny, and always honest and true.

Many of the stories hinge on those moments of realization that many of us have which can suddenly change the whole course of a life.

“Everything in life is a perilous departure,” says Macpherson, “because every life is a journey, even if you stay at home.”

She’s published non-fiction before, most notably a recent and well-received biography entitled Nellie McClung: A Voice for the Voiceless. But chatting with Macpherson gives you the distinct sense that Perilous Departures is the book that counts the most. Other works include Outlaws of the Canadian West, Outlaws and Laymen of the West and Silk, Spices, and Glory: In Search of the Northwest Passage.

“Of course, the non-fiction is very important to me and always will be because it taught me the craft and discipline of writing. But this . . . this is different.”

She’s been a reporter for CBC, worked on a number of newspapers and recalls her first assignment as a 22-year old campus freelancer for the Fredericton Daily Gleaner when she attended the University of New Brunswick.

“My first assignment was interviewing Mavis Gallant. Good lord, Mavis Gallant. The great short story writer from Paris. And she read a story that I didn’t quite understand. I was such a kid.”

The 15 stories in the book are definitely not autobiographical, Macpherson says, although her past does provide much of the background for them.

She’s lived on the Prairies, both coasts and the Caribbean and was brought up in Yellowknife, where her father, N.J. Macpherson was a highly respected and fondly remembered school principal and administrator. There are, not surprisingly then, stories that take on the various hues of the places she’s been and lived.

“I guess everything a writer writes is autobiographical in a way, but I wouldn’t say that everything in here is taken from my past.”

Still, she says, she feels that she has left herself wide open.

“Sometimes I feel like I’ve just abandoned 15 kittens on a freeway and they’re going to be hit by a semi in the next minute or so.

“Like any writer, though, I think I have created characters that are made up a little bit of me, a little bit of people I’ve met and a little bit from the situations I’ve faced.”

A frequent contributor to The Journal’s books pages, Macpherson says it’s important that the stories be accessible and meaningful to readers. They can then take from them whatever they want.

“I hope they can be read on a number of levels. I think they have a spiritual component, an intellectual component and a strong narrative component too.”

With the publication of Perilous Departures, Macpherson says she feels as if her career is just beginning.

“I’m having the time of my life with this book,” she admits. She even wrote a song that was sung at her recent book launch, and received a standing ovation after her reading. The post-launch party saw the sinking of a case of champagne by family and friends.

“I really do love the book and what it says, and I think it’s worthwhile. The photographer said he’d like to read the book, and I offered him a free copy.

“I gotta stop doing that.”

“There is wisdom and subtle wit in Macpherson and the people she has created… These stories should be savored and reread. Perilous Departures is a winner.”

“Margaret writes ” We are all part of the great mystery”. For me, this novel draws us deep into the mysteries of the sacred places of the heart where we alone know who we are, where we’ve been, the place where extreme joy and massive hurt coexist to fuel our existence. Face to face with her inner place the main character finds both strength and weakness in who she is. She experiences what truth can do, the mysterious inner resource that resides in each of us for finding freedom through forgiveness.

A marvelous read for a first novel. It engages you from page 1 and you can’t put it down.

Anyone of any age can relate to this story. We have all taken the wrong paths from time to time, we have all suffered inner turmoil from unforgiveness but have we all found the inner path to unleashing forgiveness from our spirit?”

“I haven’t read a lot of road trip books (only Volkswagen Blues and On The Road come immediately to mind), but I love the idea of them. Body Trade has additional appeal to me as the road trip sets out from Yellowknife. It eventually winds up in Belize, but through flashbacks and a side story based on a real news event of the early 70s, the north maintains a strong presence.”