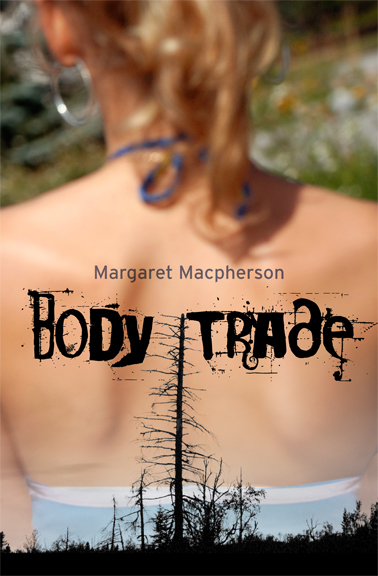

“Two women in Yellowknife decide, on the spur of the moment, to drop everything, leave their jobs and head to Mexico. Tanya, the one with the Rambler, is a world-weary white woman working in the residential school; her travelling companion is Rosie, a 17-year-old native girl. Both carry the burden of a painful past. Off they go.

It is 1973, the year after the northern crash of a mercy flight, with bush pilot Marten Hartwell having emerged as the sole survivor. This novel by Edmonton author Margaret Macpherson focuses on the journey of the two women, with the crash as a parallel story. By weaving together the two narratives, one factual, the other fictional, Macpherson delivers an intriguing tale with contemporary themes that ring true more than 40 years later.

Hartwell was taking a nurse, a pregnant Inuk woman and a 14-yearold Inuk boy from Cambridge Bay to Yellowknife for medical help. When the plane crashed, the nurse and woman died on impact, and the boy lived for nearly three weeks by eating lichen. Hartwell was eventually rescued. The subsequent inquiry, loaded with controversy and followed by the international press, is “blowing through Yellowknife like a bad spring snowstorm.” The extraordinary lengths people go to for survival is a central theme of Body Trade.

On the long road trip with many detours, Tanya and Rosie form a bond, which strengthens as they drive south and get into all sorts of predicaments. When their car breaks down, they hitchhike and sleep in all-night laundromats and make a happy detour to Disneyland. But dangers lurk ahead. As two women adrift, with only vague plans, they are open to both adventure and misadventure, mostly in the form of ne’er-do-well men they hook up with along the way. Eventually they make it to Mazatlan.

Macpherson’s story is ambitious, and tackles many issues: racism, class struggles, female friendship and white-aboriginal realities. Some of these efforts work, others don’t. The clash of the white and aboriginal points of view is sharply defined, and Macpherson effectively uses the metaphor of the landscape to describe these differences. For the whites, “the school year in Yellowknife is like the Mackenzie, one huge muddy brown river of kids that flows fast and furious in and out to school, needing to be fed morning, noon and night.” As the women drive south, Rosie marks down in her notebook the names of all the rivers they cross. The rivers came first, then the towns, she explains to Tanya.

Rosie’s trusting, sweet nature and her total lack of cynicism are no defence against the threats of the world. But through her, the reader learns a lot of the Indian way of life. Tanya, though more experienced, makes serious errors in judgment. The combination does not add up to a happy ending.

A hellhole in the jungles of Belize is the ultimate destination for these two women, and like the pilot Hartwell, they have to find a way to stay alive.

Body Trade is an unusual story that offers a unique look at the Canadian North and the people who live in it, escape from it or survive its harsh realities.”